Male Desire in the Republic: Fragile Masculinities in the Works of Yu Dafu and Mu Shiying

- Jun 18, 2018

- 6 min read

Masculinities in the Republican period (1912-49) were particularly fragile and complex due to the sweeping societal changes that occurred after the fall of the Qing Empire. In former times, educated men would have focused their time on the imperial examination with the goal of obtaining employment in the state bureaucracy. Yet, following the breakdown of the imperial system, Republican literati were left to form societies in which to develop their abilities and engage with debates over literature, politics and the nation. These societies and their magazines allowed authors to legitimise their ideas with the support of others or to rail against others for being regressive.

Yu Dafu was born in Fuyang, Zhejiang province in 1896 and received a traditional Chinese education until 1912, when he was expelled from Hangchow University following his participation in a student strike. He composed poetry through his school career and began to create fiction after moving to Japan, founding the Creation Society with other writers such as Guo Moruo. From the opening pages of Yu Dafu’s diary, the keeping of a diary is evidently linked to the legitimisation of the individual male. After moving to Japan to continue his studies into the university level, students like Yu were required to write diaries for the Department of Education to maintain their stipend. Yu wrote in 1917 on the first page: “Diaries act as mirrors of life, for great men and heroes, their words and actions, with many adequately altering prevailing customs and helping to change social conventions. If one does not record each day, then half a lifetime of achievements will simply remain on half a page in some biography in the nation’s history.” Thus writing, Yu directly placed himself within the canon of ‘great men’ who came before him (men he had encountered during his classical education), ensuring that his every action would be recorded for present and future judgement. There was no way for Yu to predict the volume of attention he would later receive following the publication of his diaries, nor would he realise the importance of his first short story, Sinking, until its publication in 1921.

Sinking centres around a Chinese male protagonist disillusioned with his studies and all those around him in Japan, neatly tying together anxieties of the individual male with the weakened Chinese nation. After the protagonist passionately quotes foreign texts, he then expresses his personal isolation stemming from perceived resentment from Japanese and Chinese classmates. He bemoans how his Japanese classmates so easily socialise with female students and swears revenge on them in future. He then departs from the urban centre, finding brief respite in the calm of the countryside, before once again falling into anxiety over the daughter of the innkeeper after hearing her in the shower and attempting to sneak a glance at her. The frustration found throughout the story variously concerns individual irritation with women and wider reflections on China’s weakened status in the international realm following the Twenty-One Demands from Japan to China in 1915 and the granting of Shandong province to Japanese sovereignty (which was only resolved in 1922). The expression of individual masculinity in Sinking is often erratic and confused, perhaps deliberately in its reflection of the complexity of changes facing young Chinese men at this time, but this too hints at an ironic distance constructed by Yu to highlight the often-contradictory demands espoused by his contemporaries.

The masculinities presented in Yu’s works only get more convoluted when tied back into his own personal writings in following years. Writing to Guo Moruo in 1923, Yu mentions a visit by Japanese reporter asking why he is so sullen. Yu responded that his glum mood was inevitable given his duty to his nation, and then turned to Guo’s criticism of the capitalist classes, expressing sympathy for their position. Further highlighting his own isolation with wider societal shifts, he stated that everyone was simply trying to survive and that the criticisms levied by Guo and others only served to legitimise their own positions. This stance by Yu brings to the fore the immense pressure on Chinese men to legitimise their positions in this tumultuous period.

In spite of his tenuous social and political position, Yu did not shy away from ruffling the feathers of those around him: he rebuffed criticism of Boundless Nights (1922) for ‘advocating homosexuality’ in a letter late that year. Some criticised him for the inclusion of homosexuality in the story, claiming it could harm young people and comparing it to bestiality before suggesting Yu himself might also ‘indulge in the same behaviours’. Yu dismissed these claims, reminding critics of the mantra “art for art’s sake” and insisting they read his works more carefully. Instead of adjusting his views to the criticism he received, Yu became more obstinate in his views and demanded respect for his individual artistic perspective. Again and again, he found legitimacy by maintaining his artistic integrity in spite of controversy surrounding him and his works.

Throughout Yu’s works, we witness countless women characters who are ‘unobtainable’ to the incapable, anxious male protagonist. This is perhaps a comment on the difficult position women found themselves in, largely excluded from education prior to the Republican period, but is also indicative of a wider male obsession within the Republican Chinese literature. Yu includes sex workers, proletarian women and others to reflect the complexity of desire within his male protagonists, who are often romantically and sexually frustrated across political and economic lines. Yu makes use of the Japanese woman in Sinking as a way of further marking emotional and sexual distance between the male protagonist and the default ‘other’ that is the female gender.

There are many male authors guilty of this othering of women through their physical objectification. Mu Shiying’s works provide excellent, stark examples with modernist, consumerist flair. Mu was born in 1912 and grew up amidst the rapid urbanisation of Shanghai under the influence of foreign powers such as France, the UK, and the USA. His later works document much of ‘modern’ Shanghai, including trams, cars, department stores and coffee shops, and often feature Mu socialising amongst other urban elites in dance halls. The fascination and obsession with the ‘modern’ is littered throughout his later works, with often include jarring instances of English words such as ‘saxophone’ and ‘neon,’ and references to advertisements of Western products like Johnny Walker whisky. The awkward juxtaposition of foreign vocabulary with Chinese text wonderfully symbolises the conflicted identities of Shanghai and its writers. The city and its populace were being dragged through ‘modernisation’ at breakneck pace – writers like Mu were subject to the pressures of these changes just like dancers forced to keep time with accelerating music, clutching ever tighter to their partners.

Although Mu’s focus on the ‘commercial’ and ‘modern’ in Shanghai may seem detached from the content of Yu’s works, there are distinct similarities between his writing of women and that of other writers such as Yu Dafu. In The Man Who Was Treated As a Plaything, Alexy is enamoured with his college classmate Rongzi, obsessing over her silk qipao and high heels. Yet he struggles to convince her to commit to him as he competes with other men for her attention. After discussing a variety of snacks enjoyed by girls like Rongzi, Alexy asks: “Have a lot of men passed through your digestive system?” He then goes on to compare himself to a chocolate bonbon to later be turned into a “waste product” and then admits the “virus of misogyny” he feels flowing through his veins.

Mu often compares the women of his stories to popular objects of the time, with one short story dedicated to a male protagonist and a desired femme fatale dubbed ‘Craven ‘A’’ after a famous cigarette brand. The protagonist even goes so far as to describe the body of Craven ‘A’ through the imagery of a map, describing her mouth as a ‘volcano’ that the locals would sacrifice men to every year, and her breasts as a pair of mountains. The imagery of Mu’s works is often shameless in its objectification of the female characters, yet it critically shows an understanding of the commercial nature of the ‘freedoms’ enjoyed by women at this time.

As Republican China worked to find its own place in the world, its male literati endeavoured to legitimise their own reputations against political, economic and cultural upheavals. The works of Mu and Yu reveal the multiplicity of pressures on masculinities throughout this period: the struggles of the individual, reformation of gender roles, and duty to one’s nation, to name but three.

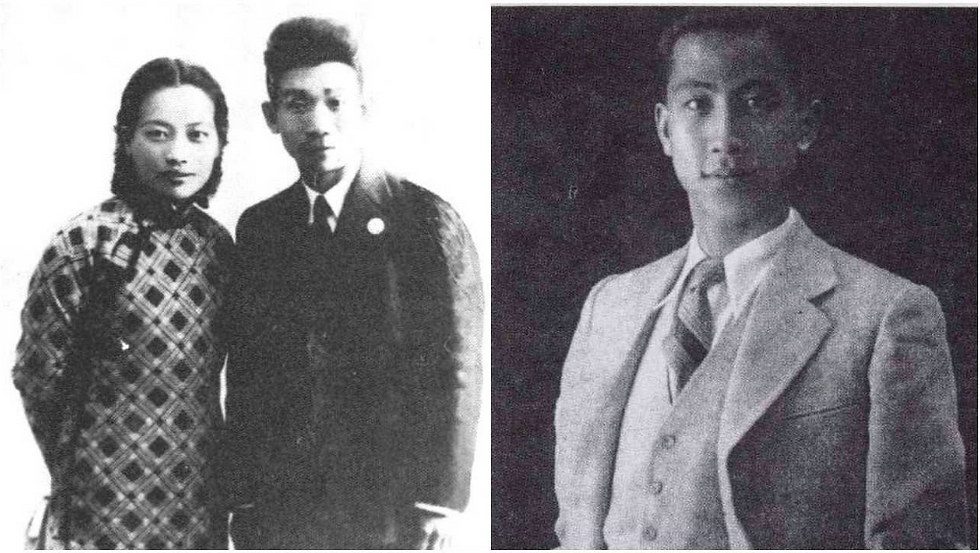

Joseph Reid is MPhil Student in Chinese Studies at the University of Cambridge. Reid began researching Yu Dafu and his expressions of masculinity at the University of Edinburgh. His research is primarily concerned with performances of masculinities in Chinese literature particularly in the early Republican period, and engages with the developments of the role of women, the effects of Western and Japanese imperialism, and literary culture, to better understand how and why Chinese men produced their literature. Images: Left Yu Dafu and Wang Yingxia, Right Mu Shiying. Images courtesy MCLC Resource Centre The Ohio State University.

Comments